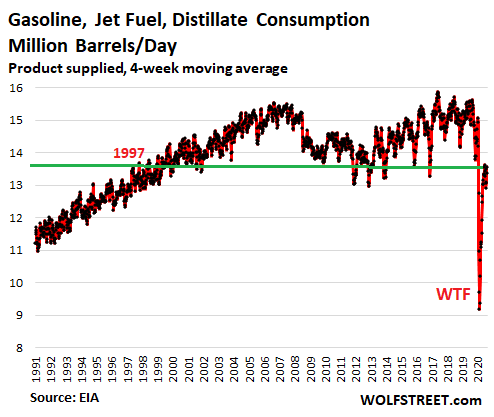

US Fuel Consumption Rises to Where It Had Been in… 1997

8 months later economy still stunted courtesy of the doomsday flu cult

While the overall S&P 500 Index is down 2.7% in October, about flat for the three-month period, and up 2.8% for the year, the S&P 500 Energy Index is down 4.4% for the month, down 19% for the three-month period, and down 50% year-to-date.

On Friday, Exxon Mobil reported a 29% plunge in revenue in the third quarter, and a loss of $680 million – its third loss in a row, the three of them totaling $2.34 billion. And it warned of possible “significant impairment” charges on “assets with carrying values of approximately $25 billion to $30 billion,” mostly related to its North American shale gas operations. The day before, it had announced job cuts of 14,000 employees and contractors globally, including about 1,900 folks at its Houston headquarters.

Chevron [CVX], which completed the acquisition of Noble Energy in early October, announced this week that it would lay off about one quarter of Noble’s employees. Those layoffs are in addition to the cuts of 10%-15% it’s planning for its own workforce. The cuts at Noble amount to nearly 600 people, and the cuts at Chevron amount to 4,500 to 6,750 folks.

Exxon shares [XOM] have plunged 53% year-to-date to $32.62 on Friday, and thereby edged closer to their March 23 decade-low of $31.45. In July 2014, at the cusp of the Oil Bust, XOM reached a high of $135, having since then plunged by 75%. Exxon’s dividend yield is now over 10%, but everyone knows that, like other oil companies, Exxon could reduce or eliminate its dividend if push comes to shove.

Bankruptcies by US shale oil and gas companies with less heft and diversification than Exxon and Chevron have turned into a flood. The debts listed in the bankruptcy filings over the first nine months of 2020 reached $89 billion and surpassed year-total filings in the prior peak oil-bust year 2016.

What these companies are facing, in addition to the horrible economics of fracking and the collapsed price of oil, which makes the horrible economics of fracking even more horrible, is the collapse in demand for oil as transportation fuel during the Pandemic, which came on top of the long-term structural demand issues in the US and other developed economies.

Eight months into the Pandemic – with infections rates now resurging – where is US consumption of gasoline, jet fuel, and distillate (such as diesel)?

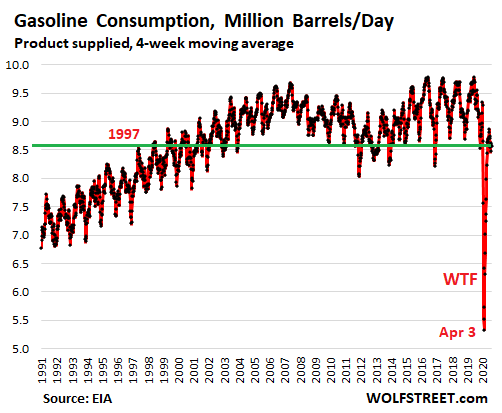

Gasoline.

In mid-March, demand in the US for gasoline had collapsed in a never-before seen manner, under an avalanche of job losses and the switch to work-from-home. In the week ended April 3, gasoline consumption plunged 48% year-over-year, to 6.7 million barrels per day (mb/d), the lowest in the EIA’s weekly data going back to 1991. The four-week moving average plunged by 44%.

The EIA tracks consumption in terms of product supplied by refineries, blenders, etc., and not by retail sales at gas stations.

As of this week, gasoline consumption, at 8.58 mb/d (four-week moving average), was still down 10% from the same period a year ago and has been essentially flat since mid-July. Gasoline consumption had first reached this level in July 1997, pointing at the long-term structural issues in demand. Over the past 12 years, including a big dip and a recovery, demand has essentially gone nowhere:

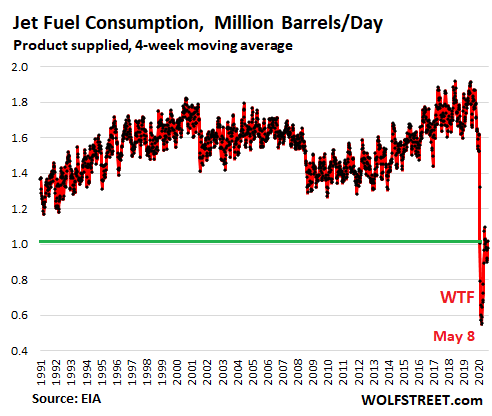

Jet fuel.

If gasoline was the good-news story – crummy as it was – jet fuel is the bad-news story. The four-week moving average of kerosene-type jet fuel consumption in the week through October 23, at 1.017 mb/d, was still down 44.3% year-over-year and remains way below anywhere in the data going back to 1991, except for the Pandemic.

Beyond the current collapse in demand – TSA checkpoint screenings of the number of passengers entering airport security zones are still down 62% year-over-year – the chart also shows the long-term demand challenges: It took 17 years for jet fuel demand to return to the 2000/2001 peak. While passenger volume recovered from 9/11 after about three years, greater fuel efficiencies of new planes that replaced the older planes kept putting downward pressure on demand.

The same thing is happening now. Airlines are massively retiring their oldest planes. And when demand picks up, they’re using their newest planes – including those they’d ordered years ago and that they will be taking delivery of. It’s all about cutting costs. It will be very tough for jet fuel demand to return to the old highs.

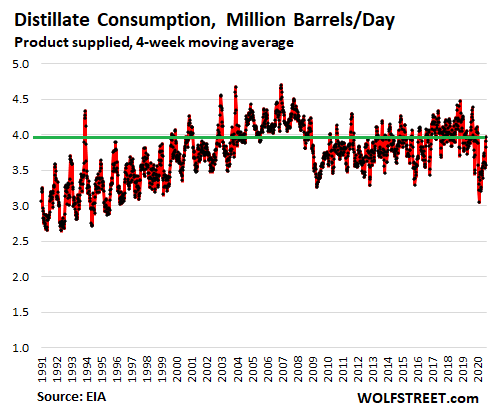

Distillate.

Distillate includes diesel for trucks, railroad engines, ag equipment, oil-and-gas drilling equipment, construction equipment, generators, etc. plus fuel oils, such as for space heating and utility-scale power generation. The four-week moving average of consumption was down 5.2% from a year ago to 3.97 mb/d – but it too shows the long-term demand declines, with the peaks having been well over a decade ago:

Gasoline, jet fuel, and distillate combined.

All combined and eight months into the Pandemic, consumption of gasoline, jet fuel, and distillate, at 13.56 mb/d was still down 12.8% from a year ago, and was back where it had first been in 1997, which makes the long-term structural issues glaringly obvious:

This is what oil companies face on the demand side in the US, in terms of transportation fuel. Petroleum is also used in the petrochemical industry, and there are hopes that demand won’t decline long-term in a similar manner. The demand situation in the US is not unique to the US. Over the past many years, Europe, Japan, and other developed economies have seen similar weakness in demand for transportation fuel. And the Pandemic has put additional and immense pressure on the US oil industry.

Source: The Wolf Street